Hawkwood was born in England, possibly in Essex, around 1320 CE, as the second son of Gilbert Hawkwood, a minor landholder.

Initially educated as a craftsman, he left home with 20 pounds and started a military career.

He fought in the Hundred Years' War under Edward III, who reportedly knighted him at the Battle of Poitiers.

When the treaty of Brétigny was signed in 1360 CE and opportunities in France dwindled, he moved to Burgundy,

worked with several mercenary companies and eventually joined the White Company.

At the time, that company was led by Albert Sterz, who moved them to Italy in 1361 CE, where there still was plenty of work for fighting men.

The mercenaries were more impressed with Hawkwood than Sterz and in 1364 CE replaced their old commander.

Hawkwood, working for Pisa, led the company in an attack on Florence.

It failed and he ended up with a severely reduced band after the Florentines bribed most of his men.

However he himself refused to be bought and served out his contract, laying down the basis of his later reputation of reliability.

Through the years he gradually rebuilt the band.

The White Company combined the traditional condottieri heavy cavalry with lighter troops like English longbow archers.

Hawkwood's troops were famous for their rapid marches, discipline and their distinctive white surcoats and banners.

Hawkwood himself led from the front, inspiring his men.

The White Company used its speed to surprise enemies and made night attacks to take towns and cities before they had gathered their wits.

It fought few field battles, but raided far and wide, with a savageness that astounded the Italians.

Like many condottieri, Hawkwood was always ready to threaten employers with pillaging if they did not pay,

or to switch sides if another party offered more money.

But he gained a reputation of reliability once committed; he always fulfilled his condotta and his men did not desert in the face of danger.

This made him popular and allowed him to sell his services for high prices.

In 1369 CE Hawkwood fought for Perugia against the Papal state; in 1370 for Milan against an alliance of Pisa and Florence; in 1372 in a Milanese civil war.

After this campaign, he resigned from the White Company, though remained active as a condottiere, working for the pope.

When some cardinals in the Vatican turned against him, he switched to the anti-papal alliance, then later switched back again.

In 1376 CE the pope granted him lands in Romagna.

As a person, Hawkwood seems to have been very much a businessman.

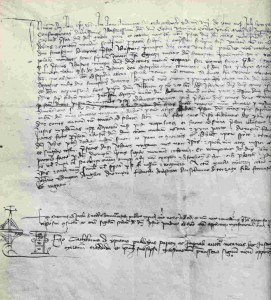

He never gained a good education and possibly was illiterate; his associates handled all the paperwork and correspondence.

He had little patience with clerks, priests and politicians, preferring to concentrate on his business: waging war.

This does not mean that he was stupid; many people who knew him recognized his shrewdness.

He was ruthless and killed people without remorse, not out of anger or malign intent, but when his bloody business demanded it.

In 1378 CE he became the captain general of Florence, fighting for the city when it was in need of his services

and pursuing other contracts when he had spare time on his hands.

Four years later he sold his lands in Romagna and bought estates near Florence instead.

The Florentines saw him as savior of their independence against the expansion of the Duchy of Milan.

In 1391 CE they gave him citizenship, a pension and added another villa to his collection.

There he lived his last years, to die in 1394 CE.

40 years later the citizens of the city had Paolo Uccello create a funerary monument to him, which survives to this day.

War Matrix - John Hawkwood

Late Middle Age 1300 CE - 1480 CE, Generals and leaders